Almost two months into our stay here in Valencia, we’ve come across a few quirks or idiosyncrasies of the city. Mostly small things but big surprises.

Beer! Despite being a huge wine producing region in a huge wine producing country, Valencians drink beer. Walk by any outdoor table on any afternoon or evening and you’ll see almost exclusively beer. In bottles, in glasses, in mugs. Yes, maybe a glass of wine or two, but beer is king.

Cooking in the streets! The city has hundreds of neighborhood social clubs (Falla clubs) that prepare all year for the March Fallas festival. They each have a social hall that opens onto the street. Apparently, anything is an excuse to party and close off the street. 1/2 year to the next Fallas. Party. Valencia Independence Day. Party. A local girl wins the Fallera beauty contest. Party. Paella is required. It has to be cooked the traditional way—on an open wood fire in the middle of the street. And snacks to nibble on? Chips, olives, pickles. And beer, of course. No fancy tapas here.

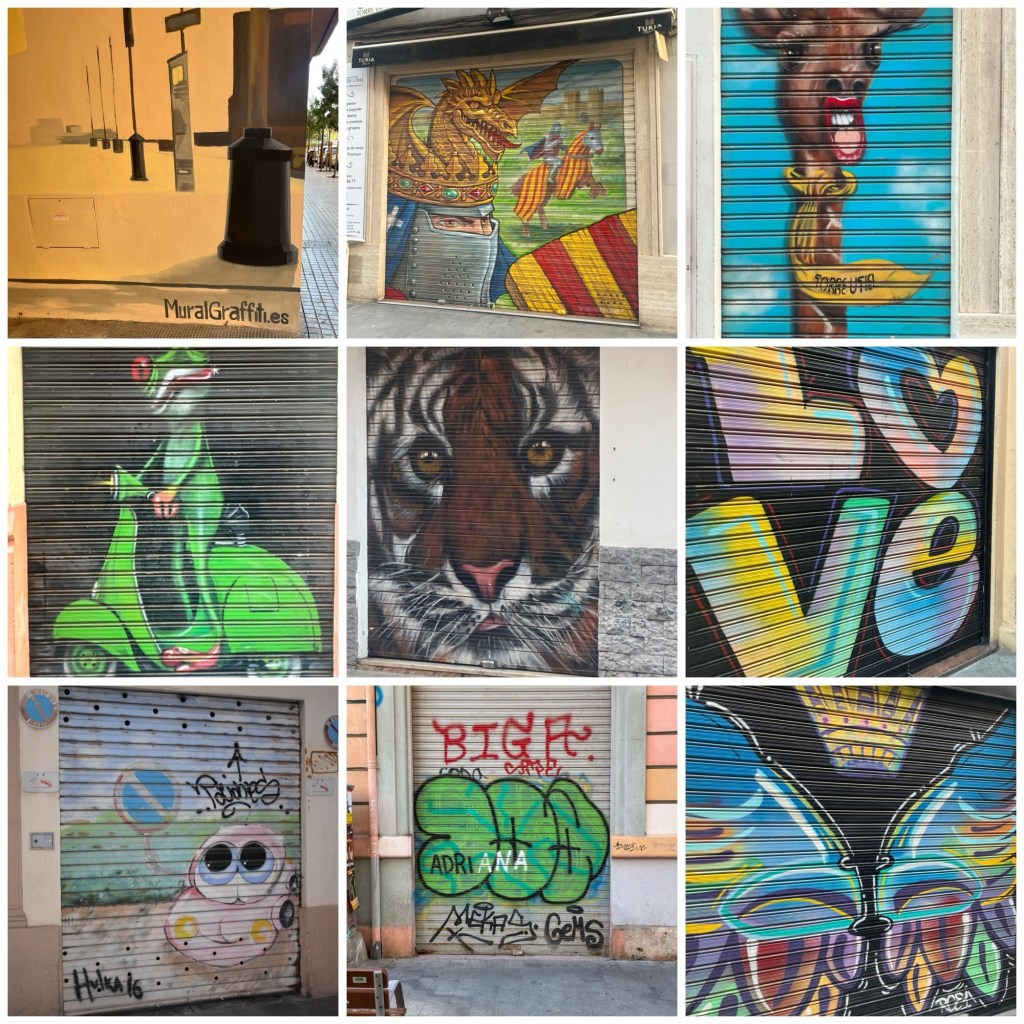

Grafitti doors! Lots of grafitti on the metal pull down garage and store front doors. Some are very artistic and beautiful—probably professionally done. Others not so much. But it’s on doors everywhere. And interestingly, very little graffiti anywhere else here in Ruzafa—although we have seen quite a bit in other neighborhoods (some called for provincial president’s resignation) and in the center of old town some anti-tourist grafitti.

Scooters, skate boards, motorized unicycles! They are a huge part of the transportation scene. And all ages use them—not just young people. The scooters travel quietly at warp speeds—they are a real menace for pedestrians. The city is flat, very car unfriendly, has special red bike lanes everywhere (which the scooters use), and the weather is good all year long. So it’s a great, inexpensive (if dangerous) solution to getting around. We followed well dressed woman as she carried her scooter into the big department store. We watched a middle aged guy come out of his big yacht at the marina and fly off on his scooter. Away he goes!

Dog washing laundromats! There are doggy laundromats for your dogs, your doggy blankets, and doggy paraphernalia. It’s a good business because everybody has a dog. One of our first nights here we ate dinner with five dogs. One breed, a kind of miniature labradoodle, is Valencia’s dog of choice. Cute little fellow seen everywhere.

Street names! They usually change after three or four blocks. Very few names seem to last the entire length of a street. We have friends who live on Literat Azorin which becomes Reina na Maria and finally Pere III el Gran. The street is 12 blocks long. This is the case everywhere in the city. No wonder cabbies look at you quizzically when you give them a street name. Better to use a landmark like a Mercado.

Merry Christmas! In the middle of October, the street decorations are starting to appear. It’s not the retail shops because they still have up Halloween decorations. Christmas starts early, and ends 12 days after Christmas with the arrival by boat of the Three Kings. That’s the big day! A present or two may be exchanged Christmas Day, but the real celebration comes on Three Kings day. Just imagine! The holiday season here spans nearly three months! American retailers—eat your hearts out.

Black Friday sales! But they are not necessarily on Friday. And they happen frequently. And there’s no Thanksgiving Day for the sale to follow. Apparently Valencia has stolen the term and uses it indiscriminately to advertise big sales

Small doors, big stores! Our two largest supermarkets, comparable to big American supermarkets, have two small doors—one on either side of a city block. A tiny sign over each entrance says Consum or Mercadona. Once you get in, the space is enormous and often snakes around in a warren of different halls and rooms. The stores literally take up a good portion of the interior of the city block. Usually there is underground parking as well. But good luck finding it.

We’ve gotten used the these quirks. And we suspect if we stayed here longer and were a bit less transient, we would find more. As one of our local friends said when we were turned away from a government building when it was supposedly open, “That’s so Spanish.” We would add, “That’s so Valencia.”